In its earlier days, Google relied heavily on plain text data and backlinks to establish rankings through periodic monthly refreshes (then known as the Google Dance).

Since those days, Google Search has become a sophisticated product with a plethora of algorithms designed to promote content and results that meet a user’s needs.

To a certain extent, a lot of SEO is a numbers game. We focus on:

- Rankings.

- Search volumes.

- Organic traffic levels.

- Onsite conversions.

We might also include third-party metrics, such as search visibility or the best attempt at mimicking PageRank. But for the most part, we default to a core set of quantitative metrics.

That’s because these metrics are what we are typically judged by as SEO professionals – and they can be measured across competitor websites (through third-party tools).

Clients want to rank higher and see their organic traffic increasing, and by association, leads and sales will also improve.

When we choose target keywords, there is the tendency and appeal to go after those with the highest search volumes, but much more important than the keyword’s search volume is the intent behind it.

There is also a tendency to discount any search phrase or keyword that has a low or no search volume based on the fallacy of it offering no “SEO value,” but this is very niche-dependent. It requires an overlay of business intelligence to understand if these terms have no actual value.

This is a key part of the equation often overlooked when producing content. It’s great that you want to rank for a specific term, but the content has to be relevant and satisfy the user intent.

The Science Behind User Intent

In 2006, a study conducted by the University of Hong Kong found that at a primary level, search intent can be segmented into two search goals.

- A user is specifically looking to find information relating to the keyword(s) they have used.

- A user is looking for more general information about a topic.

A further generalization can be made, and intentions can be split into how specific the searcher is and how exhaustive the searcher is.

Specific users have a narrow search intent and don’t deviate from this, whereas an exhaustive user may have a wider scope around a specific topic(s).

Lagun and Agichtein (2014) explored the complexity and extent of the “task” users aim to achieve when they go online. They used eye-tracking and cursor movements to better understand user satisfaction and engagement with search results pages.

The study found significant variations in user attention patterns based on task complexity (the level of cognitive load required to complete the task) and the search domain (e.g., results relating to health and finance may be more heavily scrutinized than sneaker shopping).

Search engines are also making strides in understanding both search intents. Google’s Hummingbird and Yandex’s Korolyov and Vega are just two examples.

Google & Search Intent

Many studies have been conducted to understand the intent behind a query, and this is reflected by the types of results that Google displays.

Google’s Paul Haahr gave a great presentation in 2016, looking at how Google returns results from a ranking engineer’s perspective.

The same “highly meets” scale can be found in the Google Search Quality Rating Guidelines.

In the presentation, Haahr explains basic theories on how a user searching for a specific store (e.g., Walmart) is most likely to look for their nearest Walmart store, not the brand’s head office in Arkansas.

The Search Quality Rating Guidelines echo this in Section 3, detailing the “Needs Met Rating Guidelines” and how to use them for content.

The scale ranges from Fully Meets (FullyM) to Fails to Meet (FailsM) and has flags for whether the content is porn, foreign language, not loading, or is upsetting/offensive.

The raters are critical not only of the websites they display in web results but also of the special content result blocks (SCRB), a.k.a. Rich Snippets, and other search features that appear in addition to the “10 blue links.”

One of the more interesting sections of these guidelines is 13.2.2, titled “Examples of Queries that Cannot Have Fully Meets Results.”

Within this section, Google details that “Ambiguous queries without a clear user intent or dominant interpretation” cannot achieve a Fully Meets rating.

Its example is the query [ADA], which could be the American Diabetes Association, the American Dental Association, or a programming language devised in 1980. As there is no dominant interpretation of the internet or the query, no definitive answer can be given.

Community-Based Question Answering (CQA) Websites

In recent times, Google has been prioritizing Reddit within search results.

A 2011 paper looked at the potential for using community-based question-answering (CQA) platforms to improve user satisfaction in web search results.

The study collected data from an unnamed search engine and an unnamed CQA website, and used machine learning models to predict user satisfaction. Data points used to try and predict satisfaction included:

- Textual features (e.g., length of the answer, readability).

- User/author features (e.g., reputation score of the answerer).

- Community features (e.g., number of votes).

The study found that factors such as the clarity and completeness of answers were crucial predictors of user satisfaction.

This doesn’t, however, explain the perception that Reddit isn’t a quality addition to search results and not one that should be prioritized.

Queries With Multiple Meanings

Due to the diversity of language, many queries have more than one meaning. For example, [apple] can either be a consumer electrical goods brand or a fruit.

Google handles this issue by classifying the query by its interpretation. The interpretation of the query can then be used to define intent.

Query interpretations are classified into the following three areas:

Dominant Interpretations

The dominant interpretation is what most users mean when they search for a specific query.

Google search raters are told explicitly that the dominant interpretation should be clear, even more so after further online research.

Common Interpretations

Any given query can have multiple common interpretations. Google’s example in its guidelines is [mercury] – which can mean either the planet or the element.

In this instance, Google can’t provide a result that “Fully Meets” a user’s search intent, but instead, it produces results varying in both interpretation and intent (to cover all bases).

Minor Interpretations

A lot of queries will also have less common interpretations, and these can often be locale-dependent.

It can also be possible for minor interpretations to become dominant interpretations should real-world events force enough public interest in the changed interpretation.

Do – Know – Go

Do, Know, Go is a concept that search queries can be segmented into three categories: Do, Know, and Go.

These classifications then, to an extent, determine the type of results that Google delivers to its users.

Do (Transactional Queries)

When users perform a “do” query, they want to achieve a specific action, such as purchasing a specific product or booking a service. This is important to ecommerce websites, for example, where a user may be looking for a specific brand or item.

Device action queries are also a form of a “do” query and are becoming more and more important, given how we interact with our smartphones and other technologies.

In 2007, Apple launched the first iPhone, which changed our relationship with handheld devices. The smartphone meant more than just a phone. It opened our access to the internet on our terms.

Obviously, before the iPhone, we had 1G, 2G, and WAP – but it was really 3G that emerged around 2003 and the birth of widgets and apps that changed our behaviors, increasing internet accessibility and availability to large numbers of users.

Device Action Queries & Mobile Search

In May 2015, mobile search surpassed desktop search globally in the greater majority of verticals. Fast forward to 2024, 59.89% of traffic comes from mobile and tablet devices.

Google has also moved with the times, highlighting the importance of a mobile-optimized site and switching to mobile-first indexing as obvious indicators.

Increased internet accessibility also means that we can perform searches more frequently based on real-time events.

As a result, Google currently estimates that 15% of the queries it handles daily are new and have never been seen before.

This is in part due to the new accessibility that the world has and the increasing smartphone and internet penetration rates seen globally.

Mobile devices are gaining increasing ground not only in how we search but also in how we interact with the online sphere. In fact, 95.6% of global internet users aged 16-64 access the internet through a mobile device.

One key understanding of mobile search is that users may not also satisfy their query via this device.

In my experience, working across a number of verticals, a lot of mobile search queries tend to be more focused on research and informational, moving to a desktop or tablet at a later date to complete a purchase.

According to Google’s Search Quality Rating Guidelines:

“Because mobile phones can be difficult to use, SCRBs can help mobile phone users accomplish their tasks very quickly, especially for certain Know Simple, Visit in Person, and Do queries.”

Mobile is also a big part of Google Search Quality Guidelines, with the entirety of Section 2 dedicated to it.

Know (Informational Queries)

A “know” query is an informational query, where the user wants to learn about a particular subject.

Know queries are closely linked to micro-moments.

In September 2015, Google released a guide to micro-moments, which are happening due to increased smartphone penetration and internet accessibility.

Micro-moments occur when a user needs to satisfy a specific query there and then, and these often carry a time factor, such as checking train times or stock prices.

Because users can now access the internet wherever, whenever, there is the expectation that brands and real-time information are also accessible, wherever, whenever.

Micro-moments are also evolving. Know queries can vary from simple questions like [how old is tom cruise] to broader and more complex queries that don’t always have a simple answer.

Know queries are almost always informational in intent. They are neither commercial nor transactional in nature. While there may be an aspect of product research, the user is not yet at the transactional stage.

A pure informational query can range from [how long does it take to drive to London] to [gabriel macht imdb].

To a certain extent, these aren’t seen in the same importance as direct transactional or commercial queries – especially by ecommerce websites. Still, they provide user value, which is what Google looks for.

For example, if a user wants to go on holiday, they may start with searching for [winter sun holidays europe] and then narrow down to specific destinations.

Users will research the destination further, and if your website provides them with the information they’re looking for, there is a chance they will also inquire with you.

Featured Snippets & Clickless Searches

Rich snippets and special content results blocks (i.e., featured snippets) have been a main part of SEO for a while now, and we know that appearing in an SCRB area can drive huge volumes of traffic to your website.

On the other hand, appearing in position zero can mean that a user won’t click through to your website, meaning you won’t get the traffic and the chance to have them explore the website or count towards ad impressions.

That being said, appearing in these positions is powerful in terms of click-through rate and can be a great opportunity to introduce new users to your brand/website.

Go (Navigational Queries)

“Go” queries are typically brand or known entity queries, where a user wants to go to a specific website or location.

If a user is specifically searching for Kroger, serving them Food Lion as a result wouldn’t meet their needs as closely.

Likewise, if your client wants to rank for a competitor brand term, you need to make them question why Google would show their site when the user is clearly looking for the competitor.

This is also a consideration to make when going through rebrand migrations, as well as what connotations and intent the new term has.

Defining Intent Is One Thing, User Journeys Another

For a long time, the customer journey has been a staple activity in planning and developing both marketing campaigns and websites.

While mapping out personas and planning how users navigate the website is important, it’s also necessary to understand how users search and what stage of their journey they are at.

The word journey often sparks connotations of a straight path, and a lot of basic user journeys usually follow the path of landing page > form or homepage > product page > form. This same thinking is how we tend to map website architecture.

We assume that users know exactly what they want to do, but mobile and voice search have introduced new dynamics to our daily lives, shaping our day-to-day decisions and behaviors almost overnight.

In the case of the smartphone revolution, Google responded to this in 2015, announcing the expansion of mobile-friendliness as a ranking signal – months before what became known as Mobilegeddon.

These micro-moments directly question our understanding of the user journey. Users no longer search in a single manner, and because of how Google has developed in recent years, there is no single search results page.

We can determine the stage the user is at through the search results that Google displays and by analyzing proprietary data from Google Search Console, Bing Webmaster Tools, and Yandex Metrica.

The Intent Can Change, Results & Relevancy Can, Too

Another important thing to remember is that search intent and the results that Google displays can also change – quickly.

An example of this was the Dyn DDoS attack that happened in October 2016.

Unlike other DDoS attacks before it, the press coverage surrounding the Dyn attack was mainstream – the White House even released a statement on it.

Before the attack, searching for terms like [ddos] or [dns] produced results from companies like Incapsula, Sucuri, and Cloudflare.

These results were all technical and not appropriate for the newfound audience discovering and investigating these terms.

What was once a query with a commercial or transactional intent quickly became informational. Within 12 hours of the attack, the search results changed and became news results and blog articles explaining how a DDoS attack works.

This is why it’s important to not only optimize for keywords that drive converting traffic, but also those that can provide user value and topical relevance to the domain.

While intent can change during a news cycle, the Dyn DDoS attack and its impact on search results also teach us that – with sufficient user demand and traction – the change in intent can become permanent.

How Could AI Change Intent & User Search Behavior

After reviewing client Search Console profiles and looking at keyword trends, we saw a pattern emerging over the past year.

With a home electronics client, the number of queries starting with how/what/does has increased, expanding on existing query sets.

For example, where historically the query would be [manufacture model feature], there is an increase in [does manufacturer model have feature].

For years, a regular search query has followed a fairly uniform pattern. From this pattern, Google has learned how to identify and determine intent classifiers.

We can infer this from our understanding of a Google patent – automatic query pattern generation.

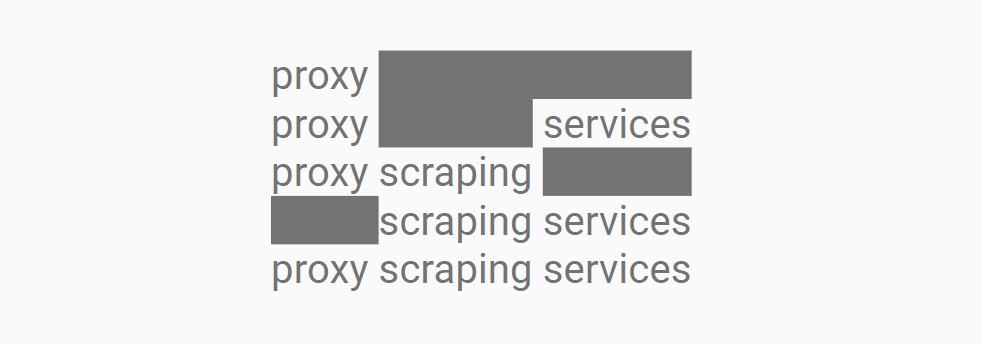

Image made by author, July 2024

Image made by author, July 2024To do this, Google must annotate the query, and an annotator has a number of elements from a language identifier, stop-word remover, confidence values, and entity identifier.

This is because, as the above image demonstrates, the query [proxy scraping services] also contains a number of other queries and permutations. While these haven’t been explicitly searched for, the results for [proxy services], [scraping services], and [proxy scraping services] could have significant levels of overlap and burden the resources required to return three separate results as one.

This matters because AI and changing technologies have the potential to change how users perform searches. It is in part because we need to provide additional context to LLMs to satisfy our needs.

As we need to be explicit in what we’re trying to achieve, our language naturally becomes more conversational and expansive, as covered in Vincent Terrasi’s ChatGPT prompt guide.

If this trend becomes mainstream, how Google and search engines process the change in query type could also change current SERP structures.

Machine Learning & Intent Classification

The other side to this coin is how websites producing different (and more) content can influence and change search behavior.

How platforms market new tools and features will also influence these changes. Google’s big, celebrity-backed campaigns for Circle to Search are a good example of this.

As machine learning becomes more effective over time – and this, coupled with other Google’s algorithms, can change search results pages.

This may also lead Google to experiment with SCRBs and other SERP features in different verticals, such as financial product comparisons, real estate, or further strides into automotive.

More resources:

Featured Image: amperespy44/Shutterstock