For the first time ever, anyone can make content in seconds.

With just a couple of prompts, an LLM can generate an entire blog post that you can publish on your website. A solopreneur or a marketing team of one can pump out newsletters, social media content, ad copy, and blog posts without breaking a sweat.

This should be revolutionary. But it has created a new problem.

Nobody can find anything worth reading.

When anyone can create, creation alone isn’t valuable anymore. Instead, something else becomes invaluable: the ability to know what’s actually worth making.

We call this taste.

Go on LinkedIn and you’ll find marketers proclaiming that “great taste is the future.” For example, here’s a tweet from HubSpot founder Brian Halligan:

I agree with them. Who doesn’t want to have great taste? But saying “you need to have good taste” is not actionable.

How does one know what good taste is? And how does one learn to develop that taste?

So, here’s my attempt to make the concept useful.

Taste is not elitism

First things first, taste is not about liking obscure things or sneering at what’s popular. Just because you vehemently dislike Taylor Swift doesn’t mean you have better taste than others.

This confusion is common and destructive. Real taste has nothing to do with obscurity for its own sake. Plenty of popular things are excellent; they’re popular because they’re genuinely good. And plenty of obscure things are terrible; they’re obscure because nobody wants them.

It’s the difference between dismissing mainstream content because it’s mainstream versus having specific, defensible reasons for your preferences. Someone with genuine taste can articulate what makes something work or fail, regardless of how many people like it.

Taste is applied judgment

It’s the ability to consistently distinguish better from worse within your domain or industry.

Doing this requires pattern recognition across quality levels. You’ve consumed enough content—the brilliant, the mediocre, the actively bad—that you can identify the hallmarks of each. You recognize when something is derivative because you’ve seen the original. You spot genuine freshness because you know what tired looks like.

Taste is a coherent framework for evaluating quality

You consume widely enough that you develop an internal system: specific traits you’ve learned signal good work (precision, unexpected connections, structural integrity) and traits that signal lazy work (borrowed framing, unearned certainty, generic transitions).

This framework is what lets you make fast, consistent decisions. When you see new content, you’re pattern-matching against your accumulated experience. Does this earn its complexity or is it showing off? Is this insight or is it received wisdom dressed up? Your framework turns vague aesthetic feelings into actionable judgment.

Taste is cultural and contextual fluency

Taste requires understanding the moment you’re operating in. It’s knowing when a particular metaphor is tired, when a topic has been exhausted versus genuinely having a moment, and what your specific audience is ready for versus what would feel jarring or obvious.

This is harder than it sounds because context is always shifting. A framing that felt fresh six months ago might now be everywhere. A topic that seemed played out might suddenly become urgent again because of new developments. What works for one audience might completely miss with another.

Ryan helping me develop my taste

Taste is compressed experience

It’s what remains after you’ve made thousands and thousands of editorial decisions, some good, some bad, and learned eventually to trust your judgment about what works.

This is why great taste is so hard to copy.

Yes, your competitors can steal your content format, your design, and even your specific article. Yes, AI can analyze your past content and mimic your style, even replicating your sentence structure, vocabulary and quirks.

But what they can’t do is to steal the judgment system that produced those choices. Your taste is opaque to outsiders because it’s built on pattern-matching they haven’t done and frameworks they don’t share. Both AI and your competitors can execute your taste, but they can’t originate it.

In return, your taste will survive platform and algorithmic changes because it’s not built on hacks. And it’ll create a raving fanbase because people want your curation, your lens, your style, and your particular way of connecting the dots.

Taste isn’t abstract nor is it a luxury. It has a measurable business impact.

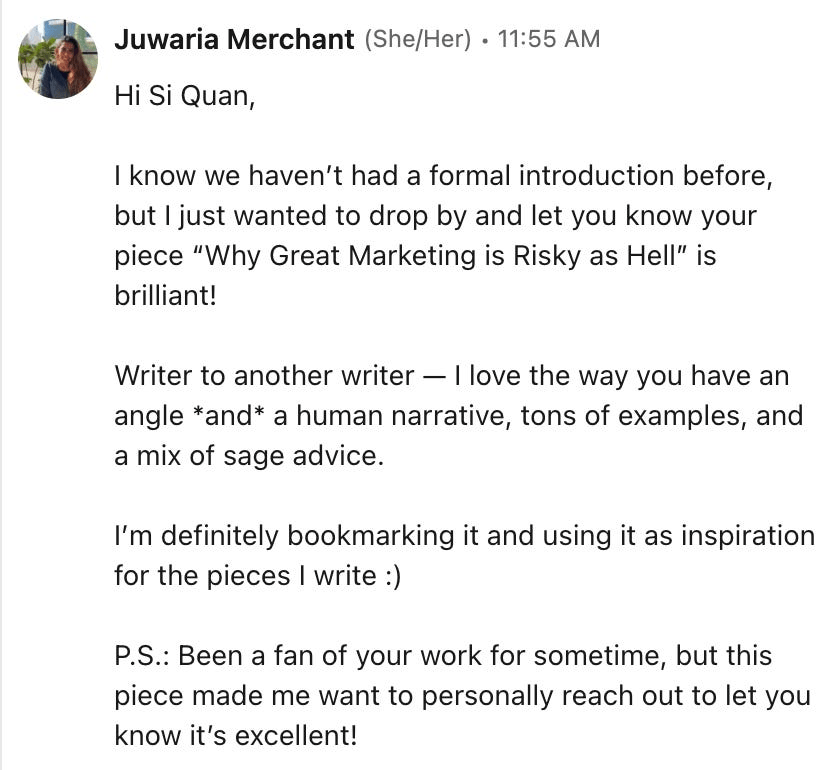

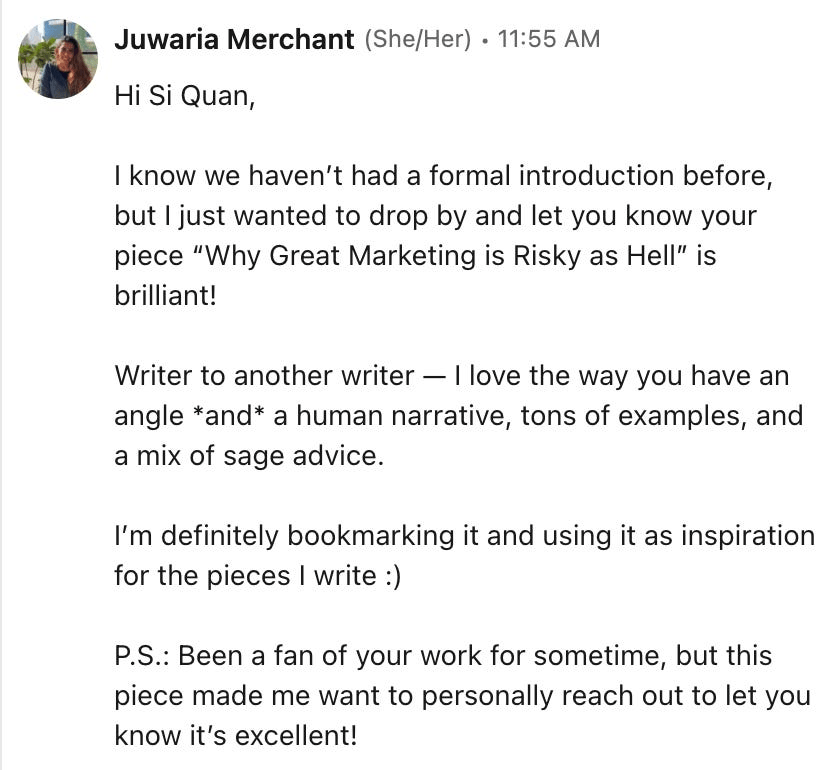

Content with a distinctive point of view gets clicked more, shared more, and mentioned more. It generates replies and conversations, not just views. People spend more time with it because it’s not skimmable filler. They return to it, reference it in their own work, and recommend it to colleagues. They DM you, telling you you’ve changed their lives.

These are signals that your content is actually landing.

So how does taste actually manifest in the day-to-day work of content marketing? It shows up in specific, practical decisions:

- Topic selection — What do you choose to cover? More importantly, what do you refuse to cover even when it’s trending? When everyone else is jumping on the same viral topic, do you have the confidence to skip it because it doesn’t serve your audience or perspective?

- Framing — How do you approach common topics in your industry? When everyone else is saying the same thing (just look at the SERPs), can you find an angle that hasn’t been cheapened yet or have the courage to say something unpopular if that’s where your judgment leads?

- Structure — How do you organize information in your content? Do you default to templates (listicles, beginner’s guides) or do you intentionally design the architecture for your audience? Sometimes your idea deserves its own unique structure.

- References — SEOs replicate top-ranking pages.. AI tends to prefer popular brands that have the most YouTube or branded web mentions. Taste means the opposite: being able to cite an obscure essay, the academic paper, or the personal obsession that creates unexpected combinations. Your reference library is a map of your mind.

- Tone — Can readers identify your work without seeing your byline? Do you maintain your perspective even when it’s unfashionable?

- Editing — Deletion is a taste decision. What do you cut? Are you willing to cut?

- Timing — Do you know when to speak and when to wait? When to ride a trend and when it’s already exhausted? And do you know when your take would add value versus when it would just add noise?

More importantly, it shows up in every member of your content marketing team.

I sincerely believe one of the reasons why our blog is well-known is because each member of the content team makes excellent taste-driven decisions.

We’re not looking for an assembly line where each content marketer fills in the blanks to hit a goal of producing as many articles as possible. We genuinely want to make great content, and we know that great content builds brand and awareness, and therefore we hyper-invest in it.

We look for content marketers who have taste and distinctive points of view, are able to defend their choices, and who’ve developed clear expertise. We hire for judgment and not just execution. And we trust each individual to make taste-driven decisions and stand for themselves.

Taste isn’t innate. You can cultivate it.

My hot take? You already have it.

After all, like me, you’re a native of the Internet. Add your years of reading, YouTube, podcasts, and even TikTok scrolls, and you would have consumed enough to begin developing an understanding of what you like and dislike.

You’ve just been duped into thinking you don’t.

So, you’d want to start by reflecting on yourself. What have you seen in your industry that you liked? And what have you seen that you think is distasteful? Why do you think that way for both your likes and dislikes?

You’ll start to understand what taste is.

Beyond that, you should also:

Consume a lot. Especially the good stuff

If you want to know what’s good, you have to consume. A lot, a lot, a lot of it.

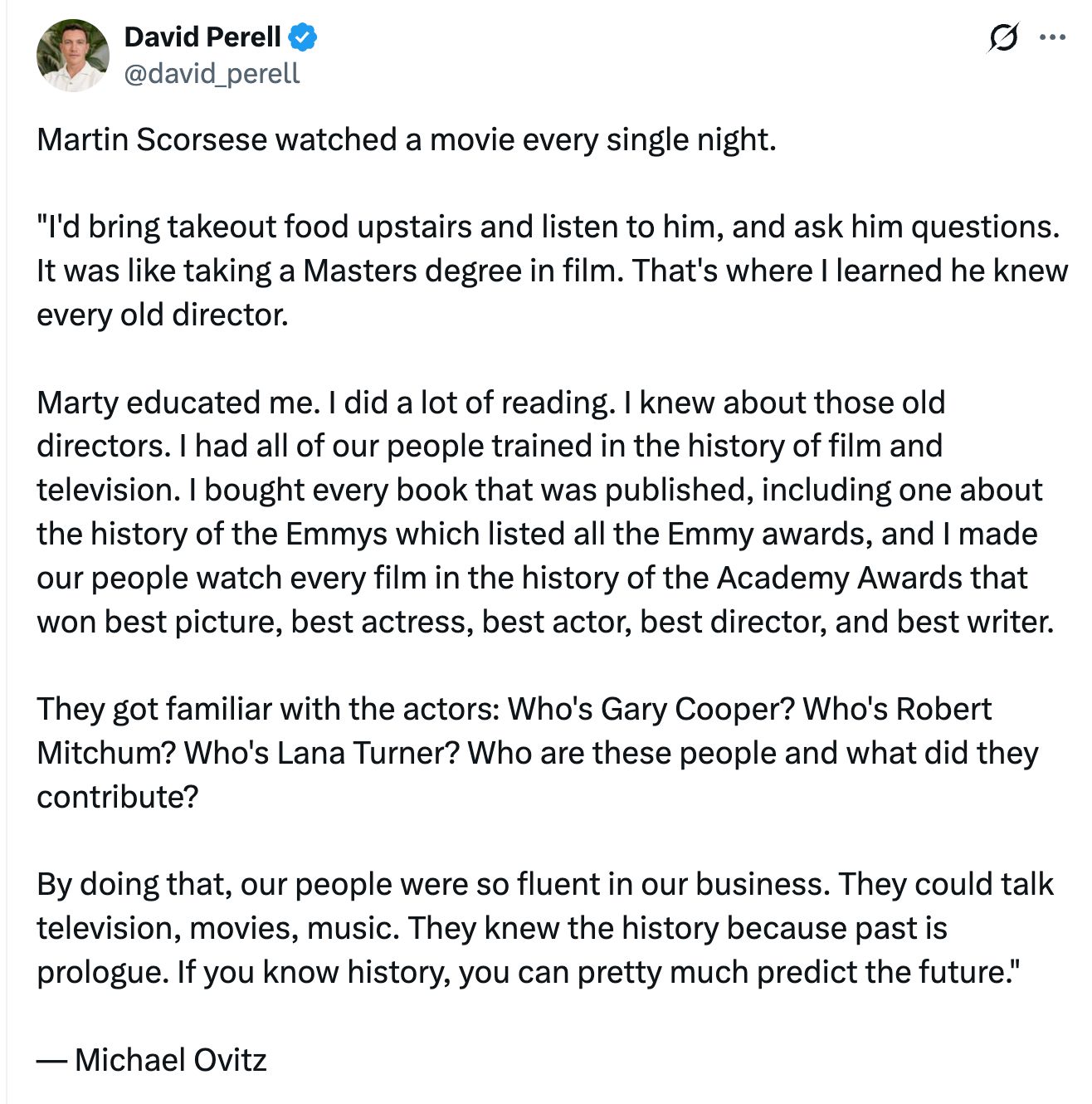

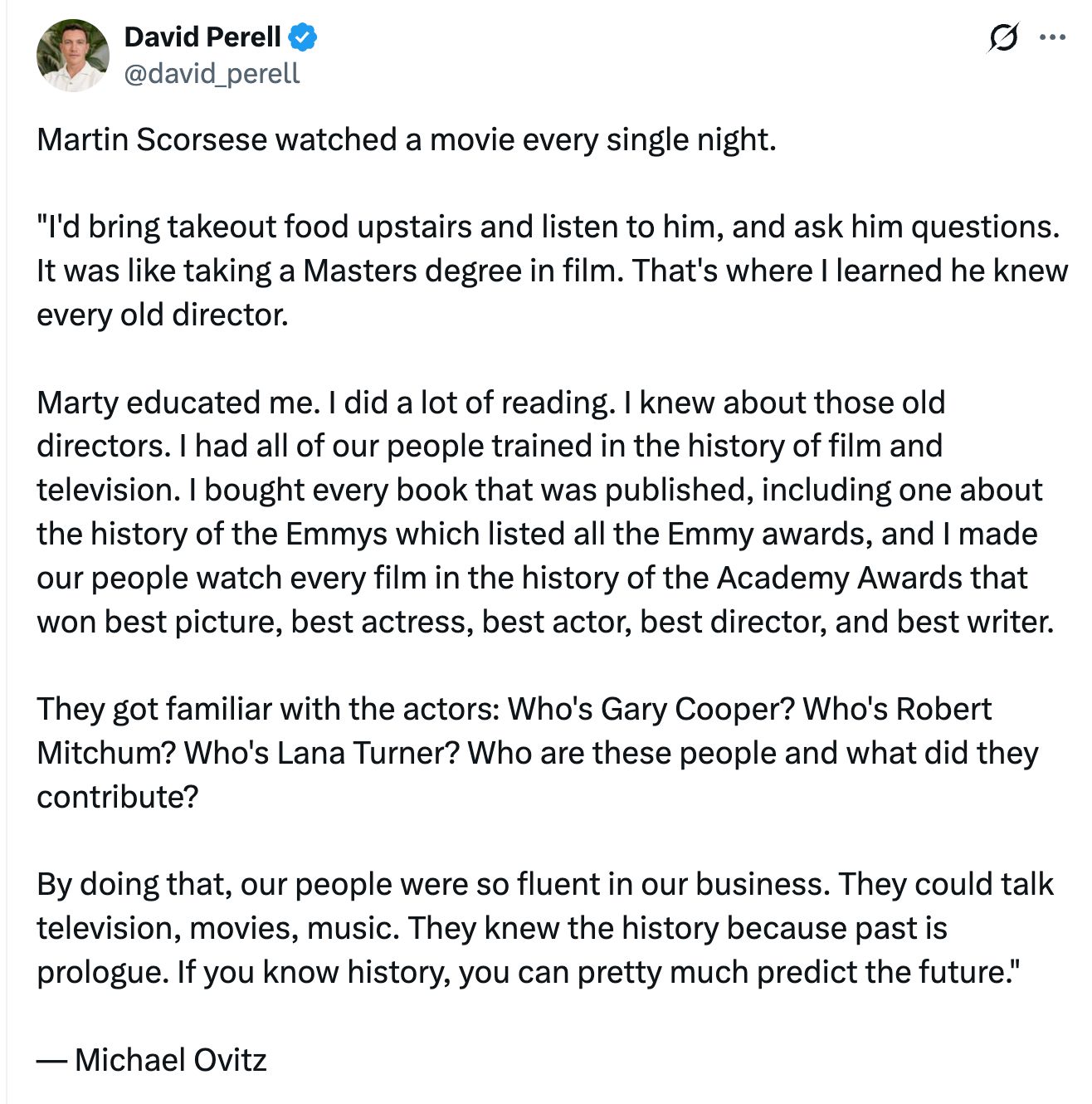

Martin Scorsese famously watched a movie every night:

If you want to develop taste in writing, you have to consume a lot of writing. No matter the format: books, articles, newsletters, magazines, and even newsletters. If you’re making YouTube videos, consume a lot of them, even TV shows and documentaries.

Be familiar with the history of your industry. There’s a reason why we’re taught to read the classics. Ideas don’t come out of nowhere; most of them are remixes of previous, older ideas.

As Michael Ovitz puts it, “if you know history, you can pretty much predict the future.”

Consume outside your job and vertical too. You want to know how I came up with this idea?

I was reading a book on free speech, and asked myself why I’m unable to produce great thought leadership content. Turns out it was because of fear. Specifically the fear of the pushback from having strong opinions. So I wrote this post as my own version of therapy.

Funny how that works, huh?

Just so you know: The best content marketers don’t just read marketing blogs. They’re reading economics, finance, history, literature, psychology, and fiction.

As Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman at Ogilvy Group, once tweeted: “The best books to read on advertising aren’t about advertising.”

Cross-pollination creates distinctive combinations. Your taste in one domain informs your judgment in another.

Examine why they work (or don’t work)

You don’t want to just consume passively. You want to understand why they’re good. Or why they’re not good. You want to be able to explain your taste, in specific details. Not “I like it” or “it was great” but “it was great because of X, Y, and Z.”

That’s probably the reason why Culinary Class Wars is one of the hottest variety programs on Netflix. The judge, Sung-Jae Ahn, may be a respected chef with three Michelin stars, but he’s also able to articulate—extremely clearly—why he thinks a dish worked or didn’t.

As you’re consuming, think about asking yourself these questions:

- Why does this work?

- What do I like about it?

- How would I improve upon it?

- What does the “me” version look like?

Put in your reps

Notice I said that “taste” is compressed experience. And guess what? If you want experience, you have to do.

There’s no way around it. You have to make a lot of editorial decisions (some good, some bad, but mostly bad) before your taste becomes reliable.

Every time you do, every time you analyze your work, you’re practicing and building taste.

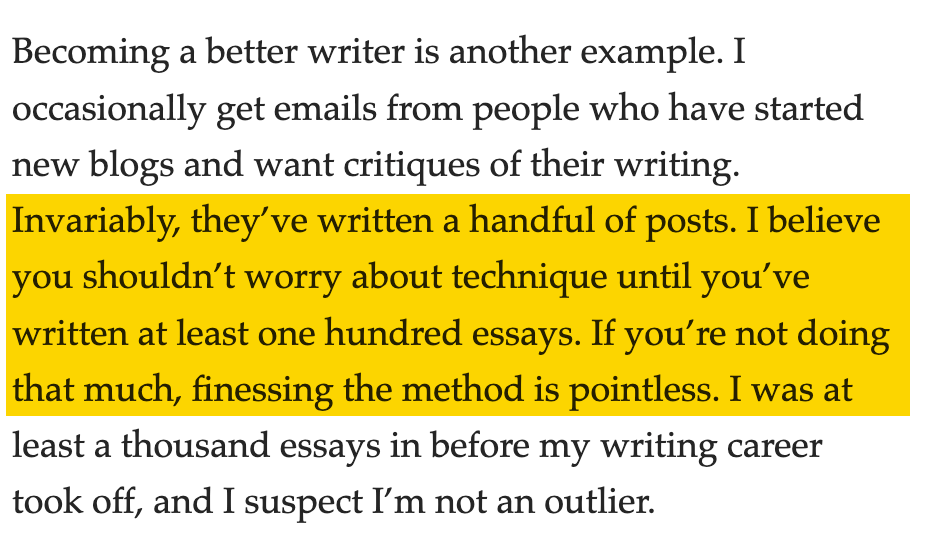

Judgment only improves with volume. You want to do 100 things. Write 100 essays. Make 100 YouTube videos. Post 100 times on LinkedIn. Create 100 TikTok videos.

As Scott Young writes:

When you’ve done 100, do more. I’m 154 articles in and I feel like I’m only getting started.

My taste is developing but it’s nowhere good yet. But trust the process, put in the reps, and it’ll come.

Create feedback loops with your audience

Even if you’re gratifying your own taste, your work ultimately needs to be seen and accepted by an audience. So don’t work in a silo and don’t work in stealth.

Put your work out there, then talk to people. Have conversations. Online and offline. What do they reference back to you? What do they share with others? What makes them reply “this is exactly what I needed”?

Having taste and a point of view isn’t to massage your ego; it is to serve your audience and help them move forward.

Accept that taste alienates as much as it attracts

“The best art divides the audience, where if you put out a record, and half the people who hear it absolutely love it, and half the people who hear it absolutely hate it, you’ve done well because it’s pushing that boundary. If everyone thinks, oh that’s pretty good, why bother making it? It doesn’t mean as much.” — Rick Rubin

If everyone loves your work, you’re probably not making strong enough choices. A distinctive point of view naturally repels people who don’t share it.

Polarisation is a feature, not a bug.

But too many people take this to mean they should intentionally create polarisation. No. Polarisation happens because you’re gratifying your taste and your genuine and sincere understanding of why something should be that way sometimes grinds others’ gears.

Not because you’re saying something controversial (even though you don’t believe it) or ragebaiting people online.

Final thoughts

The Internet removed the gatekeepers of publishing content. Today, AI has removed the gatekeepers of creating content. Production is no longer the bottleneck.

The new, scarce skill is the skill of knowing what’s worth making.

In a world where everyone can create, the only sustainable differentiation is judgment about what should be created.

Here’s the opportunity for you: most brands will use AI to chase efficiency and cut costs. They’re more than happy to sacrifice a modicum of quality and abandon taste in order to save more money. They’ll produce rivers of acceptable content that nobody remembers.

The brands that win will be the ones that slow down, that develop point of view, that make strong choices.

They’ll publish less and matter more.